The European Commission has been quietly weighing up options to radically overhaul its budget. This could see all of its 500+ biggest money pots merged into one mega money pot, divided out based on plans put together by EU countries. If approved, the move could prove seismic for European regions, farmers and rural areas – here Natasha’s Foote maps out why.

The European Commission has been quietly weighing up options to radically overhaul its budget. This could see all of its 500+ biggest money pots merged into one mega money pot, divided out based on plans put together by EU countries. If approved, the move could prove seismic for European regions, farmers and rural areas – here Natasha’s Foote maps out why.

What’s going on?

The EU powers-that-be are currently in the midst of big talks on the EU’s €1.2 billion budget, known in EU-speak as the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). And as usual, where there’s big bucks, there’s big politics – but it’s even bigger than usual this time as the budget could be in for a radical overhaul.

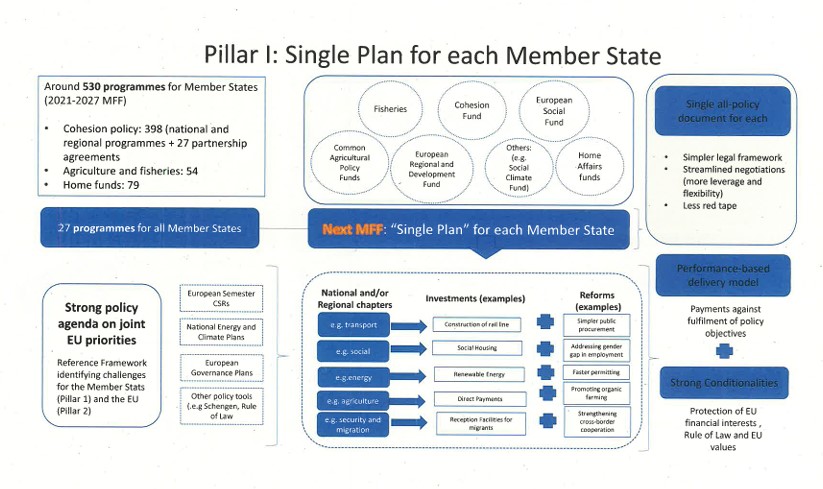

The idea is to do away with the EU’s 500+ different money pots, merging all of it into fewer, more condensed funding streams. In this way, EU funding would move away from a programme based to a policy-based approach – and this could hold huge ramifications for the EU’s approaches to rural and farming funds.

But what would this mean tangibly? According to a leaked internal presentation, originally obtained by Politico and seen by ARC, this would include merging funding from budgets such as Horizon, EU4Health and Digital, among others, into a shiny new pot of money called the European Competitiveness Fund.

Others, including the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), Regional Development Fund, Cohesion and Fisheries would also be merged. The funding would then be allocated based on national plans drawn up by member states based on their own needs and priorities and how closely this aligns with the EU’s overarching goals.

These plans would then have to be greenlighted by the EU executive before disbursing the money, with funding unlocked once states jump through the necessary policy hoops – although it’s too early to say exactly what these policy commitments could be. For the agri sector, the leaked presentation gives as the example of tying funding with the promotion of organic farming, while for the renewable energy sector it suggests fast-tracking permission.

That being said, it is clear that the plans would be evaluated within von der Leyen’s latest buzzword; ‘competitiveness’. In fact, the budgetary merge idea comes following a key report from Italian economist Mario Draghi on the EU’s competitiveness, which criticised the EU budget’s size, its conservative and bureaucratic nature and its fragmentation across the numerous spending programmes.

The idea is to create a simpler, more streamlined approach with more flexibility and less EU red tape. Its advocates argue that this will create a more cohesive, and therefore impactful, policy agenda across the different policy areas, linking key reforms with investments and focusing on joint priorities, including promoting economic growth, or social and territorial cohesion.

Déjà vu?

If you’re thinking that this sounds familiar, that’s because it is – it’s following a similar path as the last CAP reform, with each country setting their own priorities in their national strategic plans leveraging more power in member states. In this way, the European Commission can do away with accusations of imposing bureaucratic overload to member states.

Essentially, the last CAP reform was a dry run for rolling this out on a larger scale. And, from the lessons learned over the past few years, that means we can have a few ideas about how this might go, like …

A power consolidation in the apexes

The move risks a double whammy of concentration of control. On the one hand, it would shift power to the top of the Commission’s power structure into the hands of President von der Leyen, as she would be the one holding the purse strings. This gives the Commission chief more power to control the direction that member states decide to take as, if it’s not to the EU executive’s liking, countries won’t have access to the money.

But at the same time, and perhaps more crucially, the power would be concentrated into the hands of member states, who will be the hands holding the pen to write these plans. This has already sparked concerns among agrifood stakeholders, who warn against the deepening of renationalisation of the EU.

For instance, a single plan for a single programme would likely mean there is no, or very little, direct exchange between regions, rural areas and the Commission.

Instead, all demands would be funnelled through the capital. Unless accompanied with a concerted effort to incorporate rural voices, this risks policy decisions that sidelines regional perspectives or are not adequately tailored to their specific needs – especially with the focus on growth and global competitiveness.

These concerns have already seen the Committee of the Regions come out strongly in opposition to “any direct or indirect measure of centralisation within cohesion policy,” with the representation saying in an internal memo that it stands ready to “explore any legal means […] to block any attempt in this direction”. It instead argues the need to establish more legal guarantees in the post-2027 framework to ensure greater decentralisation and the “comprehensive involvement of local and regional authorities in decision-making processes”.

Regional marginalisation

This re-nationalisation could reduce the role of regions from being managing authorities to intermediate bodies or even simply beneficiaries, shaking up the division of powers between the different levels of government in many member states.

The loss of regional power would likely be particularly pronounced in centralised member states like France, and risks competition between municipalities for their share of the centralised money pot. This would be particularly destructive for bottom up approaches and programmes, such as LIFE, LEADER, HORIZON, which have for decades mobilised local initiatives, enhanced voluntary work and attracted private investments thus stabilising a rural infrastructure to create added value and income on the local and regional level.

It’s also important to note that any regional disenfranchisement not only runs the risk of misdirected policies, but also of further stoking the polarisation already seen in rural areas. With rural areas already feeling far from Brussels, this marginalisation may fuel further frustration – particularly dangerous at a time of rising populism and gains of the far right across many rural regions.

In a context of the Committee of the Regions also not being represented in the recent Strategic dialogue, the signs are not good for regional development in the EU

Less is not always more

The aim of the budget overhaul is supposed to streamline processes, with less regulation and less bureaucracy. While on paper, a single strategic plan per member state could, at least hypothetically, be in line with calls for a more strategic approach to EU funding, this all hinges on the details – and we all know that is where the devils are.

First thing to point out is that this won’t necessarily reduce bureaucratic burden, but instead shift the burden of proof from Brussels onto the backs of member states. Keeping tabs on the enforcement and control of the money will be down to EU countries – and we know from experience that this doesn’t always go well. Take, for example, leniency at member state level when it comes to enforcement of environmental rules in the CAP, or the recent critique from the EU watchdog, the court of auditors, which warns of corruption and misuse of the single Covid fund, which member states received upfront.

Similarly, after the recent CAP re-nationalisation, when Ireland tried to bring in a new ambitious option for CAP called ACRES co-operation projects – which, presciently, work on the regional level in Ireland – the IT systems were not up to the task and payments were delayed, causing mistrust and a loss of confidence in the system .

Meanwhile, this single plan design could also make it easier to change plans and priorities mid way – aka more room for member states and the EU to make it easier to transfer money between the priorities. This would perpetuate the increasing problem of the last 15 years whereby multi-annual investment programmes are thrown off course every time a new crisis or challenge appears which, in an era of perma-crisis, is more often than not.

How likely is this to actually happen?

For now, this is just one of several options that the Commission is exploring, with the EU executive currently in the process of weighing up different options and evaluating the impact this would have.

However, it seems to have won the greenlight from the top dog herself, with President von der Leyen reportedly throwing her weight behind the idea. Meanwhile, other prominent figures have already publicly got behind the idea, such as the German liberal finance minister. If the leak was intended, the moment was well chosen. With France struggling to have a government working, and Germany stumbling into possible advanced elections, testing the water may make the idea swim.

That being said, President von der Leyen has an uphill battle ahead if she wants to seriously pursue the idea, given that it is not popular with a number of other member states or indeed many regional, rural and agricultural stakeholders.

It’s true though that the farmers’ protests have given the Commission a good card to play with agrifood stakeholders. The protests which we saw at the beginning of the year were driven, at least in part, by frustration over EU bureaucracy. This way the EU executive can drop the goods and point the finger instead at member states.

To reiterate, big money always comes with big politics, and EU budget negotiations are about as big as it gets in Brussels. EU countries will have to unanimously approve the new budget before the end of 2027, but the news has already sparked the kindling that could end up in fiery negotiations to come.

More

CAP not Matching Europe’s Green Ambitions, say Auditors (again)

Brussels News Roundup – Ombudsman Launches Inquiry into CAP Fast-Track

An Agrifood Stakeholder’s Guide to the EU’s New Power Structure