Populism has become a powerful political force in Europe. The current wave of populist movements has seeped through the European countryside from France to Sweden to Poland. Yet despite the emergence of resistance and alternatives to populism, the political debate continues to overlook rural Europe. In the first of a two-part series Natalia Mamonova shares her insights into why populism is having a moment in rural areas. This is an edited transcript of a video lecture by Natalia Mamonova that was organised by the Uppsala Association of International Affairs. The lecture is based on a research project by Natalia Mamonova, Jaume Franquesa and colleagues from the Emancipatory Rural Politics Initiative. Video below.

A Quick History of Populism

There are hundreds of definitions of the phenomenon of populism, and none of them is perfect. Some scholars understand populism as an ideology, others as a political movement, or a discursive frame. But what is central in populism is the idea of “the people” who are juxtaposed against the evil, unfairly advantaged “others” – often elites or minority groups.

How does this relate to the countryside? Directly! If we look back into history, we will see that the majority of “the people” were peasants.

Peasants versus elites

The first populists were Narodniks – the political movement of the Russian intelligentsia during the 19th century. Narodniks aimed to mobilise peasants against elites. They wanted to overthrow the monarchy and create a socialist society based on the principles of the peasant commune. They failed, and we all know what happened after that….

Peasant or agrarian populism inspired the foundation of the People’s Party in the United States in the 1890s.

It was also popular in Central and Eastern Europe during the interwar period. Then, radical political parties representing peasant interests held power in Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. (Only Hungary was an exception). This period was known as the Green Rising and was characterised by the ideological and political struggles between fascism, communism and capitalism.

Restoring national glory

Talking about fascism… You might not know, but both Mussolini and Hitler won their first mass following in rural areas. And, by the way, the German minister of agriculture during Hitler’s rule was awarded the title “Riech Peasant Führer” for persuading Hitler to support peasants and villagers in order to increase votes.

The contemporary European populists are, certainly, not fascists, even though some might compare one to another. The primary difference is that fascism was oriented toward the future, European right-wing populists are oriented toward the past, or – more precisely – toward an idealised notion of the past. They aim to restore the status quo in their homelands and return ‘the national glory’ which was presumably lost due to the activities of ‘others’ – migrants, minorities, cosmopolitan elites, the EU, and so on.

But why are rural dwellers so receptive to nationalist, xenophobic appeals of European populists?

Why is Populism on the Rise in Rural Europe today?

In contemporary mainstream debates, right-wing populism is portrayed as a result of the economic and cultural crises that hit Europe during the last decade. Indeed, the global financial crisis and the Eurozone crisis have exacerbated economic inequality in rural Europe, which has influenced villagers’ support for populist parties. Likewise, the fears of losing a cultural identity due to globalisation, multiculturalism and the refugee crisis has made many people vote for populists.

However, these arguments do not explain why in Portugal – the country that hit hardest by the economic crisis – the far-right remains only marginal. Meanwhile, Poland – that has one of the fastest-growing economies in Europe – became paralysed by right-wing populism.

Likewise, if we consider the migrant crisis as the reason for right-wing populism, we would not be able to explain why the majority of rural dwellers in Switzerland voted to ban the construction of new minarets, while there are hardly any migrants in the Swiss countryside.

The fear of immigration is the easiest sentiment to mobilize and manipulate, but it is not the cause of populism.

Paradox of the populist rise

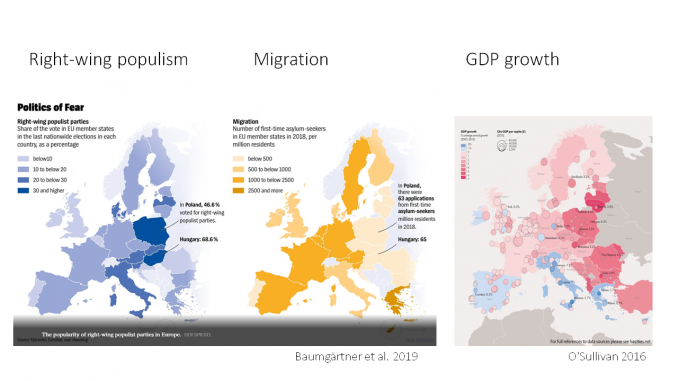

The following maps depict the paradox of the populist rise.

On the first map, you can see the electoral support for right-wing parties. The dark blue means the highest support.

The second map shows the number of asylum seekers per million residents in 2018. Likewise, the darker colour is the larger share.

And the third map presents the GDP growth. The blue colour means negative. The red – positive growth.

You can see, those countries that have the least migrants, and are better off, have the strongest support for right-wing populists.

So, if we want to understand the spread of right-wing populism, we need to go beyond the dichotomy between cultural and economic factors and to find a deeper systemic trigger.

Crisis of globalised neoliberal capitalism

In our research, we argue that the cause of right-wing populism in Europe (and the world) is the fundamental crisis of globalised neoliberal capitalism.

The last four decades were characterised by the spread of neoliberalism in different variations around the world. Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations and extends market principles in all spheres of life. It is associated with policies such as privatisation, free trade, austerity, and reduction in government spending. Globalisation and European integration also follow the logic of neoliberalism by creating a single market and facilitating international migration flows.

If earlier, neoliberalism was seen as a market-based solution to socio-economic problems, now it is criticised for exacerbating inequalities, commodification of nature, limiting the power of democracies, and eroding the social bonds and solidarities among individuals.

Neoliberalism has transformed our rural areas – and our food systems

Neoliberalism has drastically transformed the European countryside. In many rural areas, it led to deindustrialisation and de-agrarianisation. People lost their jobs and moved to cities. Many rural settlements became underpopulated. Today, 60% of European rural areas experience depopulation. Especially in Eastern and Central Europe, where more than 80% of rural regions shrunk.

But what is more striking, is how neoliberalism has transformed the ways in which food is produced, distributed and consumed! The neoliberal model of development has resulted in the expansion of large industrial agribusiness at the expense of small-scale family farmers. Let me show you a few diagrams.

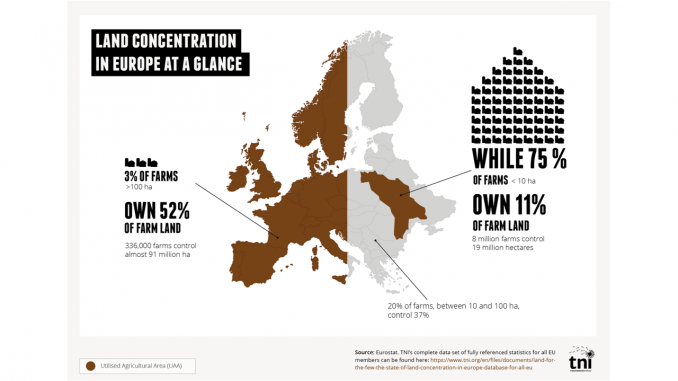

This diagram shows the scale of land concentration in Europe.

You see: 3% of European farms now own 52% of agricultural land. While 75% of small farms are left with just 11% of the land.

Many farmers found themselves trapped in the supermarket-driven value chain and tight dependency on banks and retailers. They either have to expand and become industrial food producers, or…. go bankrupt. There is an increasing rate of farmer suicide in Europe. For example, the French public health institute revealed that one French farmer commits suicide every two days. This is 22% higher than that of the general population.

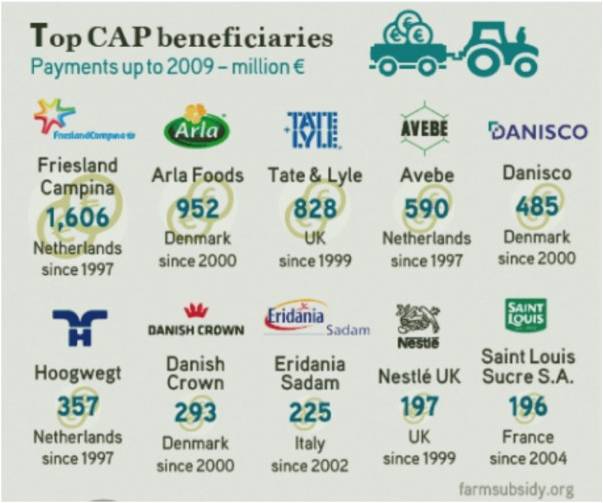

The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy is designed to support various food producers – both large and small – but, in fact, a great share of farm subsidies goes to large business.

On this slide, you can see the top beneficiaries of the Common Agricultural Policy in 2009. It’s a bit outdated, but you can clearly see that large multinational corporations received a lot of farm subsidies.

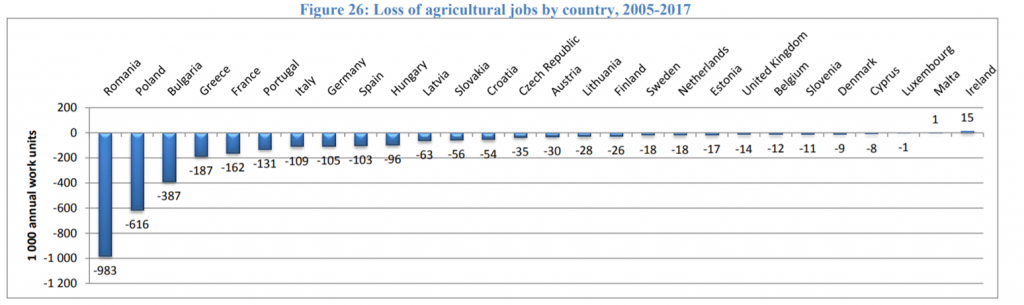

As a result, many small-scale food producers become marginalised and disappear. The next slide shows the loss of agricultural jobs by country during the last decade. Most of these jobs were on small-scale farms. Just imagine: more than 900,000 farms disappeared in Romania, 600,000 in Poland, 300,000 in Bulgaria. In total, the number of full-time farmers across the EU fell by over one third during the past decade, representing 5 million jobs.

There Is No Alternative

The crisis of neoliberal capitalism is directly linked to the crisis of representative democracies. The centre-right and centre-left parties – those that have determined European politics since the end of the Cold War – established the so-called ‘consensus at the centre’ under the neoliberal hegemony. This resulted in the disappearance from the political discourse of the idea that there is an alternative to neoliberal globalisation. Consequently, many people have come to believe that their governments represent the interests of markets and transnational corporations, while the citizens’ voice is unheard.

This belief is especially strong in the countryside, where people feel excluded from decision-making at the local, national or European levels. Politicians used to ignore the interests of the rural population for the following reasons. First, rural votes are not decisive, as villagers constitute just 28% of the European population. Second, the division between the urban and the rural is usually less pronounced in Europe and, therefore, politicians appeal to the working class, not to rural dwellers. And finally, villagers are commonly perceived as apolitical and, thus, not a reliable electoral group.

Furthermore, there are no strong farmers unions and civil society groups, which could represent the interests of rural dwellers. Although there is some increase in rural mobilisation and activism in Europe, rural protest groups remain mostly fragmented and only informally linked. The lack of solidarity and collective action can be explained by various factors.

Individualism, competition and consumerism

One factor is the neoliberal ideology that influences people’s lifestyles. It is based on individualism, competition and consumption.

Well, we all know, that the individualisation of the society limits the propensity for collective action. So does competition. I would like to say a few words about consumerism.

Consumerism became a powerful ideology and movement in Europe. It transformed citizens into consumers, thereby, limiting their political engagement. Consumers are rather passive actors, who influence politics through their consumption patterns.

Consumerism has a huge impact on the rural life – especially in the countries of Northern and Western Europe – where the majority of rural inhabitants are not engaged in food production. It is even called the “consumption countryside”.

Some authors argue that consumerism contributes to the success of right-wing populists in Europe. In consumerist societies, economic capital is important for maintaining social identities, while personal success or failure are measured by employment and welfare benefits. When people are unable to live up to salient social identities and their constitutive values, they experience low self-esteem, shame and insecurity. These negative emotions are channelled into anger and resentment towards perceived “enemies” – the migrants, minorities, elites, unelected bureaucrats in Brussels.

Watch this space for part two, when Natalia Mamonova shares her insights on populist strategies in the countryside, food sovereignty as a counterforce to these dangerous trends, and the impact the coronavirus crisis is having on right-wing populist movements and rural transformations.

More on rural transformation

Rural Dialogues | Transition Presents an Unprecedented Opportunity for Rural Revival

Coping with Covid19 – Mutual Aid and Local Responses in a time of Coronavirus

What will the World be like after Coronavirus? Four Possible Futures

Framing Farming – Nationalism, Food Security and Food Sovereignty