This article examines some weaknesses of the Association Agreement between the European Union and Central America in the context of the EU Common Agricultural Policy reform post 2020. The specific focus is on the ‘Special Treatment on Bananas’ conceded to Honduras and its interlinkages with the Common Market Organisation (CMO). The EU CMO and its import/export licences are intertwined with trade power concentration in multinational exporters, EU supermarket price pressure on banana producers, and the impact on labour rights in Central America. The article suggests that Central America countries should be subject to deeper impact assessments when signing an Association Agreement with the EU. Finally, this contribution raises some questions on the reform of the CAP post 2020.

By Melina A. Campos

1. The importance of Central America[1] in the World Agricultural Market

The story of Central American (CA) agricultural affairs cannot be told without the birth and the international emergence of the fresh fruit trade industry. With their presence in the region (from Guatemala to Panama) since 1889, American fruit multinational companies (United Fruit Company, Standard Fruit Company, and Cuyamel Fruit) built a striking empire: the fresh produce industry has endowed the region with an unprecedented infrastructure exclusively for exporting bananas to the United States of America (USA).

Colloquially, and somewhat disparagingly, CA nations are known as “Banana Republics” given the socio-political consequences that those American multinationals left behind (Bucheli, 2008). Over time, these multinationals have evolved and developed their business internationally into what we nowadays know as Chiquita, Del Monte, Dole, Fyffes, etc.

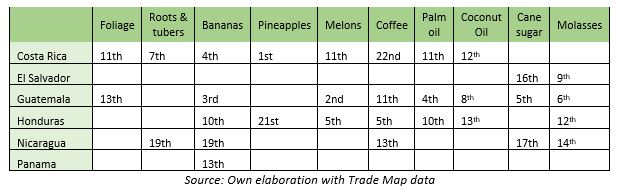

Over a century later CA is still an important player for agricultural exports worldwide. The region excels in the export of several agricultural commodities, such as coffee, fresh fruit, and vegetables, seafood, amongst others. According to the Trade Map Data[2], when consulting the 2015-2019 export data organized by Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System, commonly known as the Harmonized System (HS) in four-level tariffs, CA nations are in the top rank of exports on several products. The following table summarizes their performance:

Table 1: 2019 Ranking of Central American countries’ performance by delivering agricultural commodities worldwide (In terms of metric tons)

When analyzing Table 1, CA agricultural exports concentrate on the export of bananas, pineapples, melons, coffee, palm/coconut oil, and sugar cane and its by-products. The CA nations are between the top 20 countries producing and exporting these commodities in terms of metric tons (MT).

It is also important to mention that the mayor production locations are: Costa Rica (CR), Guatemala (GT) and Honduras (HN). El Salvador (SV), even though it is a country with a small territory, mainly focuses on sugar cane production. Panama (PA) is still competitive in the production and export of bananas. Nicaragua (NI), although it does not export as much as its neighbors, is still exporting these commodities to the EU.

2. The EU and Central America relationship: from a dialogue to the Association Agreement

Since 1960, Central America has been an economically and politically integrated region[3]. The 1984 San José dialogue constitutes the first economic and political dialogue between Central America and the EU. After its incorporation in Luxembourg in 1985, this dialogue evolved as a form of high-level political and economic annual meetings which lasted over a decade (European Comission, 1997). The first cooperation agreement was signed between both regions and came into effect in March 1987.

In 2000, the EU signed the Cotonou Agreement to commit for a policy framework which improve the welfare conditions in developing nations. With the Cotonou Agreement, the EU institutionalized the Economic Agreement Partnerships (EPAs) with the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries.

In 2005, the EU and Central America countries started to review their EPAs and give birth to a new Association Agreement (Council of the European Union, 2005). The negotiations took place between 2007 and 2010 and came into effect in 2013. Here is a summary. The Association Agreement had three underlying pillars: a) a political dialogue; b) cooperation, and c) trade (European Commission, 2012). The regional strategic paper 2007-2013 about Central America provides a more comprehensive landscape about the EU-CA relations in political, cooperation, and trade relations prior to and during the Association Agreement’s negotiation. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of the EU donor approach in the region (European Commission, 2007).

Prior to the Association Agreement, the EU granted various Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) to Central America. GPS remove import duties from products coming into the EU market from economically vulnerable countries. Different types of GSP were granted to Central America (Campos, 2016):

- 1999 – 2001: the GSP without any special arrangement/incentive

- 2002 – 2004: with special arrangements to combat drug production and trafficking

- 2005 – 2008: with special arrangements/incentives for sustainable development & governance

- 2009 – 2011: without any special arrangements/incentives

- 2012 – 2013: without any special arrangement/incentives.

The EU typically sign Association Agreements in exchange for political, economic, trade, or human rights commitments in a country. In exchange, the country may be offered better trade conditions (e.g. tariff-free access) to some or all EU markets and financial or technical assistance.

When comparing the GSP schemes (1999-2013) and the Association Agreement between the EU and Central America, the market access conditions did not change for pineapples, melons or palm oil, simply because these products were not subject to any import duties from the EU side. For bananas and coffee, which were import sensitivity products (i.e. products that are socio-economically sensitive to free competition), market access conditions were upgraded, and trade restrictions were relaxed with the conclusion of the Association Agreement.

3. Analysis of the EU-Central America’s Association Agreement (and links with the CAP)

This section describes how some aspects of the CAP, namely the export licences with third countries established in the Regulation 1308/2013 on the Common Market Organisation, which were became implicitly negotiated in the Association Agreement with Central America countries, are linked to the banana export sector in Honduras.

3.1 The case of export licences for Honduran bananas

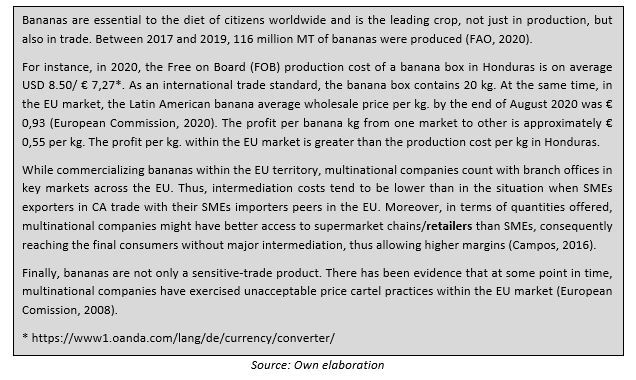

Central America countries deliver 20% of the region’s bananas production to the EU market, some of which is then also re-exported. In 2019, Belgium and the Netherlands were the 6th and 7th banana exporters worldwide[4].

Bananas are still a sensitive traded product between both regions. Thanks to the Association Agreement, Central America countries were granted a special treatment with tariff rate quotas. This allowed a pre-determined quantity of a product to be imported at lower import duty rates (in-quota duty) than the duty rate normally available for that product. As of 2020, the EU will cut its tariff to 75 €/t compared to 114 €/t applied since 2017. Central American exporters must apply for an export licence for being able to export bananas to the EU market. The issuance of such licences has been a duty of the Ministries of Commerce of the Central America region.

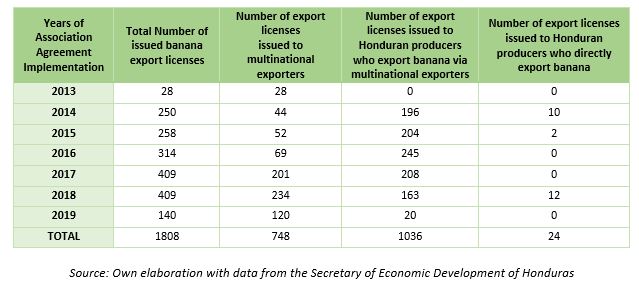

Statistical data provided by the Secretary of Economic Development of Honduras[6] confirms that in the years of implementation of the Association Agreement with the EU, a high number of banana export licences were issued in favor of multinational companies.

Table 2: Overview of Honduran banana export licences issued under the Association Agreement with the EU

Between 2013 and 2019, from a total of 1808 export licences, 748 were issued for multinational exporters. And 1036 licences were issued to Honduran producers that supply their bananas to multinational exporters. This represents a high concentration of trade in multinational exporters.

“In 2019, out of 140 banana export licences, 120 were granted to multinational companies and their suppliers.”

According to a former Chiquita employee, today active member and ex-president of the Honduras National Banana Producers’ Association (Asociación de Productores de Bananos Nacionales), both Banana production and export in Honduras is still in the hands of multinational companies (Personal communication, September 29th, 2020). Usually, multinationals do not just possess own crop parcels, but also buy bananas from Honduran growers. Although multinationals still own the banana export infrastructure in Central America, Honduran producers can apply for individual export licences. However, their banana production is usually sold to multinationals who can thus consolidate exports and organize the sales process for the EU market.

As the table No. 2 provides evidence, very few Honduran banana growers export directly to the EU. This market situation does not reflect the desired Association Agreement’s trade welfare objective to strengthen the market access for Small and Mid-size Enterprises (SMEs) in Central America. Title III on social development and social cohesion, article 41, section b) of the agreement literally supports this point:

“trade and investment policies, bearing in mind the link between trade and sustainable development, fair trade, the development of rural and urban micro, small and medium enterprises and their representatives organizations and to corporate social responsibility” (European Union, 2012).

In view of the development of the Honduran banana export sector, it is essential to deliberate how this production and trade model can contribute to rural development, fighting poverty, and reducing inequalities and exclusion. On the other hand, the current developments at a production and trade level framed within an Association Agreement highlight another relevant topic regarding Central American land use. Thus, this contribution brings up the reflection if the Central American soils will be seen only as productive areas that generate immediate benefits for the multinational companies and, given the market forces, indirectly exclude the SMEs.

In addition, there are other market aspects to consider such as the pressure that both EU traders and retailers exercise on developing countries’ exporters. Usually, such price pressures are transmitted to producers and not traders; after all, traders work under commission basis (Campos, 2016). For example, Ecuador, as the largest banana producer in Latin America, emphasizes the issue by rejecting the Aldi banana prices (Fruitnet, 2019). It is important to mention that market access conditions of Ecuadorian bananas in the EU market are similar to the Central American mechanism. The Oxfam study “Sweet Fruit, bitter truth” also points out the responsibility of the German supermarket chains in pressuring banana producers in developing countries, thereby the chains can import bananas all year round at very low prices (Oxfam Germany, 2016).

Overall, the sensitivity of the banana case arouses several questions that deserve a thorough scientific and political examination:

- Since bananas have always been a sensitive traded product and in the majority of the cases they have been produced by multinationals, why has the EU always highlighted and marketed banana trade preferences and their market access conditions as a very important step in the trade relations between both regions? Why was an Association Agreement necessary for this when production conditions have not substantially changed?

- After seven years of implementation, is the Association Agreement a policy tool relevant for the SMEs banana producers in Central America, taking into account that today, multinational companies continue to control the trade flows and receive main trade benefits?

- Can the EU, through the CAP reform of its Common Market Organization Regulation, incorporate better trade mechanisms and provisions that create a win/win situation for developing countries and include their SMEs structure, especially when operationalizing market access activities for sensitive products such as the Honduran banana case in the frame of an Association Agreement?

- To what extent will EU banana producers continue to be recipients of sectorial types of interventions in the new CAP reform? And, in which ways do such interventions compete or find synergies with sustainable banana production and trade in Central America?

Box 1: How does the banana trade works within the EU and why is it so lucrative?

3.2 Other spill overs: Workers’ rights

3.2 Other spill overs: Workers’ rights

Recently, a study conducted by the International Labor Rights Forum, the International Union of Food Workers (IUF), the Latin America Regional Secretariat (Rel UITA), and Fair World Project, with support from 3F International, uncovered the labor conditions of Fyffes subsidiaries in Honduras. Fyffes plc is a billion dollar, Japanese-owned fruit and fresh produce company headquartered in Dublin, Ireland.

Foxvog & Rosazza[6] documented how Honduran workers on Fyffes’ melon farm have been subject to precarious work conditions. The report unveiled the following practices: workers in their sixties or seventies, who have worked over two or three decades are not subject to social security system; reported rampant wage theft with salaries below the minimum wage established by the Honduran government; inhumane working conditions such as occupational injuries and fainting during labor

hours given the extreme weather conditions, and exposure to toxic agrochemicals. Similar work conditions occur in the banana industry. Likewise, the Oxfam study „Sweet Fruit, bitter truth“ (SÜSSE FRÜCHTE, BITTERE WAHRHEIT Die Mitverantwortung deutscher Supermärkte für menschenunwürdige Zustände in der Ananas- und Bananenproduktion in Costa Rica und Ecuador), exposed the poor labor conditions of banana and pineapple farm operators in Costa Rica and Ecuador (Oxfam Germany, 2016).

For the CAP reform post 2020, there has been a lot of discussion about the environmental and climate standards of EU imports, especially in the context of the EU Green Deal. However, it is important for the European Commission to develop stronger mechanisms that impede EU companies to import agricultural goods from farms that are faulting on labor rights.

Labor conditions are also an issue within the EU. The documentary “Europas dreckiges Ernte” exposed this market failure on labor rights within the EU territory and the deficiencies of certification standards/bodies, with certified Spanish and Italian companies infringing on migrant’s labor rights (ARD, 2019), (Foxvog & Rosazza, 2020).

It is important to point out that multinational companies might exercise different policies in different countries. In Costa Rica and Panama, multinational banana producers/traders such as Chiquita and Dole develop sustainable banana production projects, even supported by international cooperation agencies[7]. It may well be the case that labor conditions for banana workers have improved and are better than in Honduras. But again, the question arises: have multinational companies operating in Costa Rica and Panama at some point in time violated labor rights and benefited from the Association Agreement trade conditions?

Recently during the 2020 edition of the “Green Week”[8] trade fair, German Supermarket chains agreed on better labor rights and decent living wages for workers on banana fields in developing countries (BananaLink, 2020). This is a voluntary measure that hopefully is aligned with the German initiative for a new supply chain regulation (Initiative Lieferkettengesetz[9]) and contribute to the improvement of the labor conditions situation in all Central America countries where multinationals are operating. This is an important step considering that the existent infrastructure and logistics in Central America banana fields belong to the multinational companies. After all, this is a 100 years old business in their hands and we believe they will not allow newcomers to make a rapid incursion in the business, says a German fruit importer (personal communication, June 2013).

On a global scale, this is a plausible step on behalf of the German supermarket chains. After all, these chains control around 50% of food distribution via supermarkets within the EU (Metro AG, 2015), and are a vital distribution mechanism for delivering bananas to EU consumers. In this sense, the German Supermarket chains are the “multinational customers” and have the bargain power to change multinational exporters’ business philosophy. When this measure endeavoured at the Green Week is straighten with the new German initiative for a supply chain regulation (Initiative Lieferkettengesetz, 2019), it will probably become the right market force for demanding a change in farm operators’ labor conditions at banana plantations worldwide.

4. The CAP and how the EU can improve the Association Agreement with Central America

In September 2020, Mr. Peter Altmaier, current Minister of the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, in his role of Coordinator of Economic/Trade affairs of the German Presidency of the EU 2020[10], presented the priorities of the German Presidency on Foreign Trade affairs of the European Council to the European Parliament (European Parliament, 2020).

During the INTA Committee meeting, many Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) raised several questions on sustainable supply chains within and outside the EU. In his view, Mr. Altmaier believes that the EU should counterbalance the extent to which it needs to consider every single foreign trade issue concerning sustainability in order to facilitate the signing of more Association Agreement deals between the EU with other nations.

But, in disagreement with Mr. Altmaier’s point of view, it is necessary that the EU conduct more impact assessments when negotiating an Association Agreements, especially in the interest of both parties and to deliver a proper accountability on the trade pillar for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in alignment with the EU sustainability principles. Simply because the favorable prices of imported agricultural products, with high intermediation margins within the EU market cannot continue to be leveraged in the policy of reducing costs to the detriment of the exploitative working conditions of farm operators in developing countries. Such as the case of the Honduran tropical fruit exports in the hands of multinational companies.

When assessing possible interlinkages between the CAP and the Honduran agri-food supply chains, the Policy Brief Checking the Chain: Achieving Sustainable and Traceable Global Supply Chains Through Coordinated G20 Action is a valuable source suggesting how rigorous legislation on a national levels could safeguard international alignment for enabling more transparent supply chains and implement due diligence (Spertus-Melhus & Engelbrechten, 2020). The development of such policies on a G-20 level are also in accordance with the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on unfair trading practices in business-to-business relationships in the food supply chain (European Parliament, 2018).

When negotiating any Association Agreement, the EU could develop other mechanisms for developing countries that are equivalent to the trader database mechanism established in Art. 10 of the Commission Implementing Regulation No. 543/2011 on fruit and vegetables and processed fruit and vegetables sectors, especially when applied to exporters gaining market access to the EU.

Coupled with the previous points, compliance in the attainment of transparent agri-food supply chains in developing countries should be part of the EU Green Deal strategies (e.g. Farm to Fork strategy) for assuring a fair economic return for farmers/producers and improving their welfare situation.

The CAP reform should consider the recommendations proposed by civil society organisations, such as the Policy Brief ‘Raising the ambition on global aspects of the EU Farm to Fork Strategy’, which pledges for seven key strategies for enabling the transition towards sustainable food supply chains. Some of these recommendations can definitely help to rectify the situations of Honduras and Central America banana supply chains when trading with the EU (CIDSE, 2020), (European Commission, 2020).

Melina A. Campos is an agribusiness independent consultant active in Central America. Her specialization in Sustainable International Agriculture with a focus on Agribusiness and Rural Development is coupled with over 15 years’ work experiences on trade relations between the European Union and Central America.

[1] Central America is politically integrated by the Republics of: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama.

[2] https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx

[3] The evolution of Central American Integration process can be found at the Organization of American States library: http://www.sice.oas.org/SICA/instmt_e.asp

[4] Data compiled from https://www.trademap.org

[5] https://sde.gob.hn/

[6]www.laborrights.org/fyffeshondurasreport

[7] https://www.rewe-group.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/1452

[8] https://www.gruenewoche.com/

[9] https://lieferkettengesetz.de/

[10] https://www.eu2020.de/eu2020-en

Download this article as a PDF

This article is produced in cooperation with the

This article is produced in cooperation with the

Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union.

More on CAP Strategic Plans

CAP | Parliament’s Political Groups Make Moves as Committee System Breaks Down

CAP & the Global South: National Strategic Plans – a Step Backwards?

CAP Strategic Plans on Climate, Environment – Ever Decreasing Circles

European Green Deal | Revving Up For CAP Reform, Or More Hot Air?

Climate and environmentally ambitious CAP Strategic Plans: Based on what exactly?

How Transparent and Inclusive is the Design Process of the National CAP Strategic Plans?