Miles King

It seems inconceivable that it was only a year ago when the UK was due to crash out of the EU under a no deal Brexit. Thankfully that crisis was averted. Leading up to that momentous non-event, I wrote about what might happen to our food supply in the event that our smooth trading relationship with the EU broke down utterly. One year on, we find ourselves in a remarkably similar position – thanks to a Pangolin, or rather thanks to people wanting to eat Pangolins and turn them into medicine. Don’t blame the Pangolin.

Our food supply is part of a small number of “essential” things on which life depends. Food, water, housing (and the means to heat it when it’s cold). That’s it. Anything else we might like to think are essentials – well, we are just kidding ourselves. That includes mobile phone signal, the internet, even twitter. It wouldn’t be much of a life, but those are the things which ensure we remain alive.

While we have a plentiful supply of water (far too much in some places after the record breaking rainfall of the winter) and increasingly our electricity supply is provided by reneweable energy sources, we are still dependent on fossil fuel gas to heat our homes. Some of that comes from the North Sea still but much is pumped to the UK from Norway or, indirectly, Russia. The supply lines remain intact and there’s no reason to think that will change for the foreseeable future. There is no shortage of housing either – its just that like so many other resources, it’s allocated very unequally. The Govt, after long doing nothing to prevent a mushrooming in the numbers of homeless people on our streets, has now decided that the homeless must be housed, as a matter of urgency. It’s given the task to Local Authorities, who are supposed to have, by now, found emergency accommodation, in hotels emptied by the Pandemic. That the Government forced those same hotels to place their staff on furlough, before deciding that they were needed, after all, is just another example of the Government lurching from one reactive response to another. That is in the nature of crises though.

Which brings us to food. Previously, in the pre-coronavirus (PCV if you like) world, lots of people eat out, bought take-aways, bought ready-meals and cooked. Many relied on foodbanks. Not because of a shortage of food, but because of poverty. Food was plentiful. Supermarket shelves groaned under the weight of it. Want to buy an apple? Here, look at 15 different varieties from all over the world.

UK farm produce went to supply factories producing ready meals, to supermarkets (though only a few apples were UK grown), but it also went into the foodservice sector. Foodservice is, or rather was, a massive sector using UK farm produce and imports. I’ve been trying to find figures for how much UK farm produce ended up in meals provided by everyone from MacDonalds to the Roux Brothers. It’s tricky. For dairy, AHDB estimated that foodservice took 8M litres of fresh milk a week, 8% of total UK production. conversely, of course, domestic demand for fresh milk has soared, placing additional pressures on suppliers and the supply chain. Large dairy business Mueller, which recently laid off staff, is now desperately trying to recruit 300.

The beef in beefburgers, the potatoes for chips in fish and chips, the Lamb going into Indian restaurants, all of these supply lines have stopped, practically overnight. Some of this will be redirected into the delivery trade (deliveroo etc), but PCV 80% of the foodservice sector was eating out. You just can’t redirect that much food into hom e delivery.

For some food products then, there’s a big surplus being built up, because people are not eating out any more, but the supply chain is yet to be reconfigured to convert that produce into a form in which it can be transported and packaged for supermarkets. This is happening now, but under pressure from a number of sources. The main one being lack of workforce. We’re already hearing about shortfalls in the workforce because of sickness and self-isolation. This applies across the entire supply chain, from farm workers, pickers and packers, delivery drivers and shop workers. That our food industry was already so dependent on overseas workers (both EU and non-EU) (again remember Brexit?), who are now stuck unable to travel due to coronavirus lockdowns, has only further exacerbated an existing crisis.

So for some domestically produced food there’s a surplus and a blockage in the supply chain. As a result Lamb prices have collapsed, because people are not eating out, and exports being disrupted. Under a no deal Brexit, it was predicted lamb prices would drop 30%. Coronavirus has seen them drop 36%. For the lamb industry, Coronavirus is no-deal Brexit by another route. I’m going to make a prediction here. People are not going to start buying up the surplus of lamb to cook at home. It isn’t going to happen, even if there was a big campaign to get people to buy and eat lamb ( because there have been many over the years). Even if lamb was being given away free with every pint of milk, it probably wouldn’t make much difference. I think the nation has fallen out of love with lamb.

Anyway we aren’t going to run short of meat. We’re more than self-sufficient in beef, lamb, chicken, pork. We may have to change our habits and start eating chicken brown meat, instead of demanding that we must have white. Again, all of this was predicted in the context of a no deal Brexit. It’s almost uncanny, as though Coronavirus has come along and said

“you know all those predictions about a no deal Brexit screwing up your food supply chain? Well predict no more. I’m here to show you how it plays out.”

But, as well all know (or almost all of us anyway) meat is not an essential part of our diet. We do have to eat fruit and vegetables though. And this is where it gets really tricky, because we import around 75% of our fruit and veg. Much of that comes from Spain, the Netherlands and Italy. So while we will have potatoes for a while (they were lifted last Autumn), we rely on imports for things like tomatoes, peppers, onions, garlic, lettuce, courgettes and cucumbers. Tinned tomatoes from Italy.

And again, as if Coronavirus was some spectre of no-deal Brexit, the two countries hit hardest by the virus in the EU, are Spain and Italy. Exports of fruit and veg from Spain rely on workers being supplied to the vast acreages of horticulture in southern Spain. workers driven to farms in minibuses. Shared minibuses, full of Moroccan workers. Morocco is now also suffering a large CV outbreak. Morocco has closed its border with Spain.

This is happening across Europe. Seasonal workers, which are the backbone of the food supply system, are unable to travel, or unable to work through sickness and self-isolation.

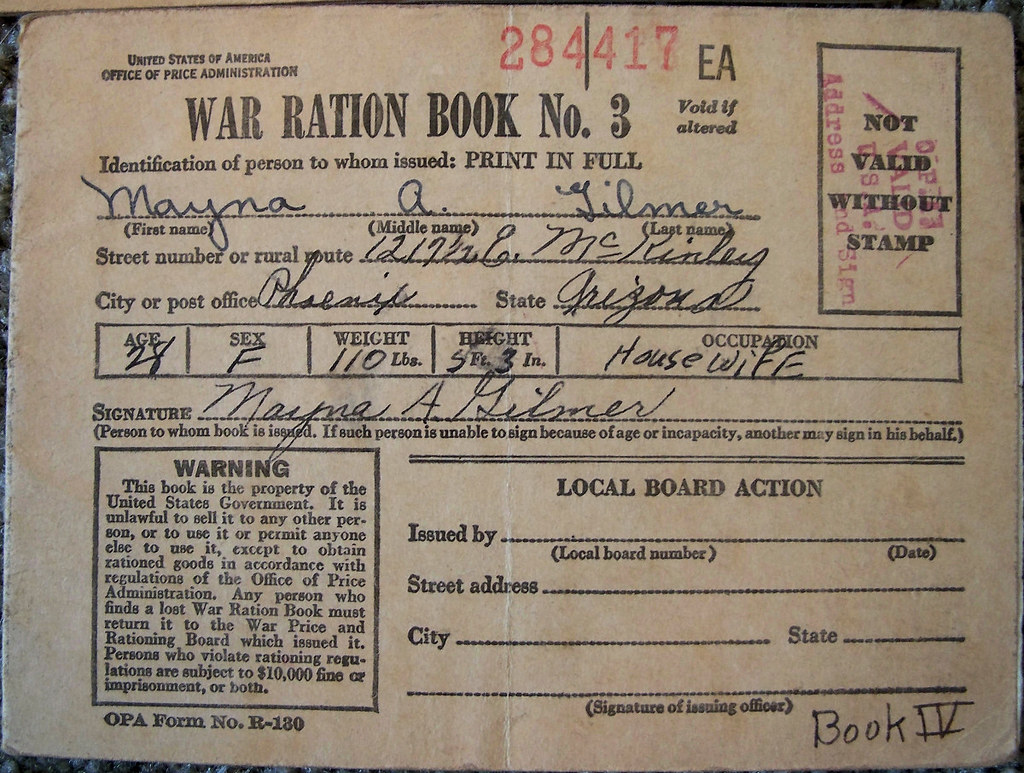

Food policy experts Tim Lang and Erik Millstone have already called for food rationing to be introduced, not by the supermarkets, but by the Government. They are usually right, and they are right this time. Rationing needs to be combined with a voucher system that ensures those in greatest need (and the poorest) have access to the most nutritious food, regardless of income.

Rationing is needed for three reasons – firstly because the food bank system providing food to those who cannot afford it, has been overwhelmed and the Government must step in to stop people going hungry. This has been exacerbated by schools closing, preventing free school meals from relieving some of the hunger pressure.

Secondly because the supply chain problems I have described are rapidly coming down the line towards us and essential supplies of fruit and veg are going to dwindle.

Thirdly, perhaps most importantly, is because everyone has to have as healthy a diet as possible and we need to ensure that food is distributed fairly and equitably. A healthy diet means a healthy immune system, which helps people to cope with illness, like novel viruses. Fruit and veg provide our bodies with the vitamins, minerals and micro nutrients which keep our immune system functioning properly. Oily fish is also essential for the same reasons. At the moment, food is not flowing to where it’s needed; it’s still flowng according to who has most access to the system and that’s partly down to income. While the Government has gone some way towards guaranteeing people’s incomes after the income they previously derived from work has disappeared (almost overnight), there are still huge holes and delays in the system.

A rationing and voucher system would ensure that everyone was able to get the food they need, without having to worry about whether they could afford it.

What else can we do, as individuals? Those of us lucky enough to be in a position to do so, need to crack on and grow as much food as we can, as this will reduce pressure on the system. And, until rationing comes in, everyone else needs to make sure they don’t throw away any food that can be eaten, which means only buying food that’s definitely going to be eaten.

This article first appeared on Miles King’s a new nature blog

More on ARC2020

Framing Farming – Nationalism, Food Security and Food Sovereignty

UK | Coronavirus: Rationing Based on Health, Equity and Decency now Needed

Coping with Covid19 – Commoning as a Pandemic Survival Strategy

Council of Ag Ministers meet on Covid19 | Green Lines, State Aid, CAP Extension

Coping with Covid19 – Tensions in Farming, Trade and the EU Institutions

Coping with Covid19 – the Open Food Network and the New Digital Order(s)