We are told today that agriculture and rural areas are living through a pervasive digital transformation. But will digitalisation reverse the current productivism model or perpetuate it? At 72nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Regional Agricultural and Forestry Economics (ARAFE), Matteo Metta presented his insights on digital agriculture from the rural perspectives. The hybrid event took place last 23 October 2022 at the Ryukoku University (Kyoto, Japan) and touched upon key issues, global trends and local realities in agri, food, and rural transformations. The international symposium discussed about how agroecology become a product quality claim in Europe or how to manage water resources in Japan local communities. The discussions and insights of the event are summaries in this paper. ARC2020 thanks the Journal of Rural Problems for publishing Matteo Metta’s insights in this article.

> This article was first published on the Journal of Rural Problems. Click here to download it.

Introduction

Increased farm specialisation is recognised among the megatrends that are deeply affecting the structure and resilience of European Union (EU) and worldwide agriculture and rural areas (Debonne et al., 2022; Susanna and Tuomas, 2022).

Farm diversification is a farming style in itself, but also an effective response to this megatrend (Dimopoulos et al., 2023; van der Ploeg et al., 2002). There are different layers of farm diversification in agriculture, from farming diversification (e.g., mixed cropping) to on-farm and off-farm diversification activities.

We refer to “on-farm diversification” when family farms or members of an agricultural holding perform extra-farming activities that are directly related to the farm: e.g., food processing, direct selling, agritourism, renewable energy production, social farming, ecosystem services, and much more creative examples (e.g., on-farm theater performances, community gatherings, seed savings).

The contribution of on-farm diversification to farm viability, but also to the integration of agriculture into rural wellbeing and the broader regional development has been widely acknowledged by policy makers and scholars (Hubbard and Gorton, 2011; OECD, 2020; Ward and Brown, 2009). Nevertheless, the scale of on-farm diversification remains very marginal so far, at least in the EU.

Herein, the share of farmers engaged in other gainful activities is used as an indicator of on-farm diversification (Augère-Granier, 2016). More than 10 years ago (2013), only around 7% of all EU farms were engaged in at least another revenue stream connected to, but outside farming (Bock et al., 2020).

Another megatrend effecting agriculture, food, and rural areas is digitalisation (FAO, 2021). Whether dealing with issues in Africa, Europe or Asia, digitalisation is often depicted as the pathway towards development and sustainability.

Against this context, I ask whether the ongoing digital transformation or digitalisation can amplify diversification in agriculture and what are the risks and opportunities that it entails. This heuristic review is based on literature and field experience gained during my research in Europe and Japan. It contributes to identifying key themes and questions for scholars and policy makers engaged in responsible digitalisation for agriculture and rural development.

Source: Prof. Yasuo Ohe

Digitalisation and internalisation: risks and opportunities

In industrialised and global market-based economy, Jackson et al., (2021) argue that the commodification of food and agriculture prevails over other policy narratives that are centered around human right or common goods. Within a neo-classical economic framing, internalisation is defined as the process whereby non-tradeable externalities jointly produced with agricultural goods are integrated in market mechanisms, such as price, supply, and demand (Ohe, 2019).

Three examples of internalisation are discussed: 1) Credits for environmental services (e.g., carbon removal); 2) Digital branding and marketing (e.g., social farming label); 3) Servitisation (e.g., e-wine tours). Although carbon farming is an example at the borderline between farming and extra-farming activities, it is discussed here to draw lessons on some of the broader issues around digitalisation and internalisation.

Credits for environmental services

The race for carbon credits in agriculture is considered one of the most promising win-win incentives to fight climate change and increase farm viability in one shot, no less. In the last years, digital infrastructures and technologies like satellite data, software, modellings, blockchains, sensors, unmanned vehicles, APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) are being assembled with regulations and networks accompanying this data-savvy process of internalisation. The data flows behind the measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) processes are at the core of carbon credits and markets.

Private or nationally accredited carbon removal certifications like the Label Bas Carbon in France or MoorFutures in Germany rely more and more on data extraction, storage, modelling, visualization tools to monitor carbon practices, stock, flows, and markets. Just recently, the European Commission published its proposal1 to set carbon credits and markets on a common legal basis across the EU. Despite the promised opportunities to create new revenue streams for farmers, the logic and socio-technical aspects of these certifications and credit-based transactions have been received with criticisms by peasant farmer organisations and environmental NGOs, as carbon farming can entail quite a few limitations and side-effects.

Credits: Tommy/RéseauActionClimat

The transparency, openness, interoperability, and real meaning of data-driven certifications in terms of cutting the level of emission remains questionable or problematic (e.g., double counting, additionality, permanence, or non-reversibility are some of the technical issues). As pointed out by peasant farming organisations (Coordination Européenne Via Campesina, 2022), the financial logic behind carbon farming is to institutionalise carbon emissions for the benefit of polluting economies and large-scale landowners. Carbon’s global price volatility and monetary dynamics (deflation, inflation) that are typical of financial assets should inspire caution against the risks it poses on farmers’ livelihoods, land prices, and food access. Other issues to consider are data-grabbing and increasing financialisation of natural resources.

Yet, policy makers and industrial players in the EU are steering research in this direction and creating the regulatory conditions to install this new business model despite the fact that the cost-benefit distribution among large vs small landowners, data companies, local communities, and public authorities leaves us with some open questions: who will be the ultimate winners and who will bear the costs? Will market mechanisms reduce overall emissions or just serve to maintain control powers in financially rich economies?

Source: Matteo Metta

Digital marketing in social farming

If our soils are getting thirsty for carbon, our fields are starving for labour. While technology and machinery continue to displace workers in both manufacturing and services, the integration of workers with disabilities in our society is left in the hands of shrinking public subsidies, ethical entrepreneurs, and active civil society organisations operating on a voluntary basis. Depending on the national legislations and customary practices, social farmers are farming and producing food while also providing social services for rural and urban dwellers, such as integrating people with disabilities in farm operations, as well as people with burn out, victim of sex and gender abuses, asylum seekers, substance use disorder (SUD), or individuals with justice system involvement.

Again, in a market-based economy, creating certifications or labels for products issued by social farming is a way to make this model more viable and prone to capture a premium price that internalises positive externalities (e.g., social cohesion, education, health). Equally important, these efforts can give more visibility to social farming and raise awareness among people.

As an illustrative example of these efforts, in 2019, the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries developed Noufuku JAS, an official label recognising ethical standards and the social value of agriculture-welfare collaboration.

Source: https://noufuku.jp/know/jas/

On the other side of the world, in Italy, most of the recent political efforts on food labels have been targeted against the decision to impose an EU-wide Nutri-score label, however, some talks have started to emerge on the risks and opportunities of creating an official label for valorising social farming products2. This multi-stakeholder debate was sparked after the revision of Italian law n. 141/2015 for social farming in the summer 2022, which finally extended its scope to the inclusion of immigrants as part of social farming services.

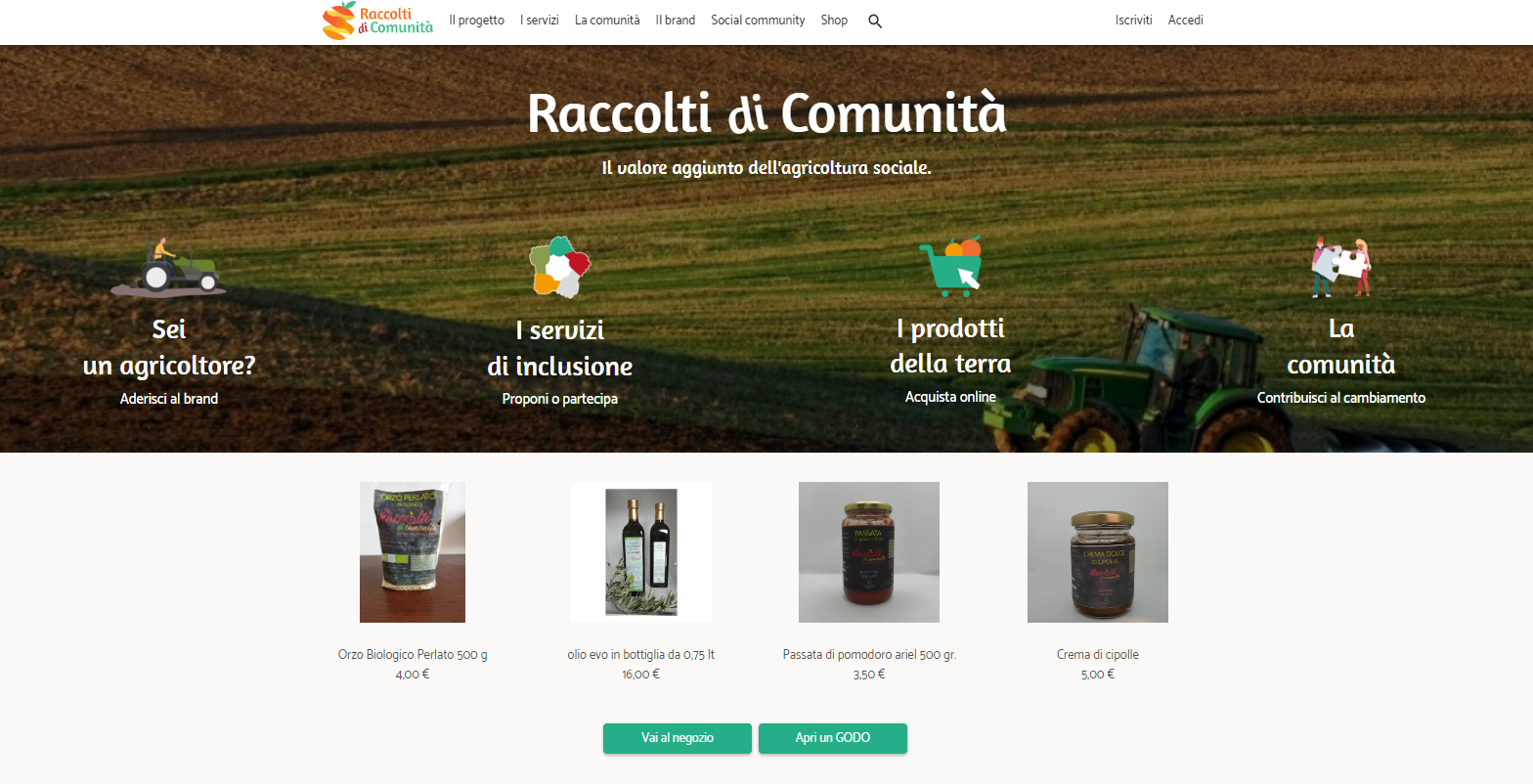

Although there are no nation-wide official labels for social farming across the EU, private and voluntary brands for social farming products already exist also outside Japan, for instance “Raccolti di Comunitá” in Umbria Region, Italy. In a market and society saturated by labels and slogans, the questions and concerns of farmers is whether these tools mean something to the consumers, achieve their goals, and overcome the incurred costs. From the public authorities’ perspective, official labels mean also more responsibilities to control and possibly dispute resolution over infringements. The answer could be that labels (alone) need more work to become effective, or in some cases, miss the whole point.

The digitalisation of social farming sales can play multiple roles here. I describe at least two. First, it can help farmers in branding and marketing, i.e., understand demand, create graphics and brands, personalise service, analyse performances, and promote labelled and non-labelled products with cheaper and more scalable tools. Second, alternative food networks using internet platforms to group multiple farmers’ products can easily extend their list of filtering categories to promote labelled and non-labelled products issued by social farming. Next to “organic”, “local”, “pesticide-free”, online platforms can add “social farming” categories or at least add information links with social farms. When searching for marketing spaces in existing online platforms, there will always be ambiguities to address: is it ethical to sell social farming products on commercial, globalised, large scale online platforms selling also products from polluting or dehumanising farming? Or is it wiser to create a separate online markets just for social farming? Or maybe just bypass the online trade?

In Umbria region (Italy), Raccolti di Comunitá (my translation: “community harvests”) created their own online website and app to amplify a nation-wide community around social farming products and services. A private, voluntary brand and chart were created to internalise the ethical value and raise awareness about social issues at stake in farming and agricultural products (see https://raccoltidicomunita.it/il-brand for the brand). The brand has been embedded into a wider (hybrid) platform of real-life and virtual services, information sharing, community interactions.

In spite of these concrete opportunities, social farmers believe that the most valuable and rewarding relationships are nurtured by real-life meetings with the health operators, people with disabilities, and the final consumers, which often happen in very short, localised food supply chains (e.g., weekly markets or on-farm shops). A click cannot replace these moments, so as a label cannot communicate the authenticity and unique stories of social farming, especially when personalised and direct links with farmers can be dissolved, recreated, and then appropriated by multi-national food companies that try to create virtual connection between consumers and farmers via QR codes or other smart phone applications for their corporate social responsibility. As argued for other farm management practices (Zscheischler et al., 2022), digital transactions and mediums could also contribute to the homogenisation of the countryside and farm experiences.

Rather than replacing the real with the virtual, light digital tools like online websites or social media platforms can enrich deep relationships and diversity in rural areas. Digitalisation could complement, assist, or simplify the technical aspects of organising localised, human, direct, in-person meetings. In the case of social farming, rather than fully digitalising food sales and in-person relationships, there are platforms in Ireland (https://www.socialfarmingireland.ie/) or Flanders-Belgium (https://groenezorg.be/) where digitalisation addresses another prominent need in social farming: the reduction of high administrative workload and paper required from a farmer to provide these social services or receive a public subsidy. However, research in the field of e-governance for various on-farm diversification activities is generally scant, particularly in social farming.

Servitisation (e.g., e-wine tours)

In a digitalised economy, farmers engaged in on-farm diversification have another technological option to create product-service systems (PSS). The shift from a product-centric to a service-centric business model is called servitisation (Kohtamäki et al., 2021). One of the constraints of internalising positive externalities from agriculture or rural services like tourism is the spatial and temporal simultaneity between their production and consumption (Ohe, 2019). However, in certain conditions, digitalisation might stretch out and overcome these spatial and temporal boundaries. Here an example.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, the agritourism farm “Enclos de la Croix” in France have experimented the provision of e-wine tours. In e-wine tours, groups of consumers bought online and received different bottles of wines produced by the farm directly to their home.

The consumers paid for the extra-farming service of meeting the farmer online, while tasting the wines, learning about the quality properties, and walking through the farm together with the farmer – spatially disconnected but still temporarily simultaneous. Other examples are farmers-led YouTube videos or virtual communities around farming live-sessions (e.g., beehives, poultry).

While one could reasonably argue that this e-business could be just a niche experiment targeted mainly to urban, middle-class consumers during the special lockdown circumstances, it can be useful to understand how some rural business ideas or community projects can change or find alternative means when good quality infrastructure and internet connectivity is accessible, online meeting platforms are widely used, and farmers have a wide range of skills, resources, and partners to conceive, delivery, and retain value in rural areas.

Online food platforms do not only let consumers select and buy food products, but also add new services like door-to-door delivery, click-and-collect options (farm drive-in), share the suggested cooking recipes, stories, and reviews. Specialised platforms or single farm websites can inform visitors about the time to visit a farm, give geolocation information about how to reach the farm, automatically translate website text, connect people with a wider community, or even collect online payments for booking a farm visit, class, or village tour.

Though digital servitisation in agriculture could be presented in general as a growth and innovation strategy to reinvigorate a declining agricultural sector, in practice, it may lead to a uberisation of agri-food workers, disneylandisation of farms, develop new digital troubleshooting demands for farmers, or add to digital fatigue among consumers. In some cases, servitisation can camouflage a larger and long-established trend in industrialised economies of increasing use of fossil-fuel energy, shifting production of raw agricultural commodities and inputs abroad (wheat, seed oil, feed, fertilisers), and concentrating internal agri-food businesses on more remunerative models.

Source: Matteo Metta

Discussion

Internalisation between risks and opportunities: two weights, one measure?

The process of internalising externalities conceals both risks and opportunities, and the integration of digital components in this process is far from being frictionless or purely technological. Given this short overview, one of the follow-up questions is how to go about risk and benefit assessments of digitalisation. There are no straightforward answers, but it is important to try to clarify these questions beforehand, especially when we try to involve different actors in this collective exercise. How likely are these perceived risks and opportunities? What happens when different actors see risks and opportunities in different ways? Which opportunities matter more and for whom? Can monetary and economic arguments be the leitmotif to take decisions on digitalisation towards on-farm diversification? And more importantly for follow-up actions, how do we ensure that high-tech companies, platform investors, and policy-makers change their decisions based on science, research, and the rural actors’ concerns?

Internalisation: at what conditions?

Internalisation does not happen overnight. Ohe (2019) proposes a step-by-step approach to understand and navigate these processes. Other innovation researchers put more emphasis on the wider institutional ecosystem and the role of brokers and innovation agents in orchestrating these interactive processes (Klerkx, 2008). Others put more emphasis on individuals’ entrepreneurship and their marketing capabilities (Lokier et al., 2021; Yoshida et al., 2019). In my view, there are both digital and non-digital options and conditions that are necessary to consider before farmers, communities, or public authorities manage to internalise their positive externalities.

We might be tempted to assume that a new software or access to internet connectivity, digital skills, hardware, and digital technologies in general are essential conditions for on-farm diversification. However, this will give an impartial picture of the reality, which is skewed towards those who push or benefit from digitalisation because they fit well into its mechanisms and conditions.

To benefit from digitalisation, diversified farmers need to spend time and resources for building a digital profile and ecosystem adapted to the history and directions of the farm. Digital skills and technologies are not plug-in functions downloadable with a click and installable just after a training. They are to be considered as new digital tasks requiring working units in situation of labour shortages, high wage taxes, young brain drain, labour volatility (e.g., woofers, part-time workers) and super-aging population in rural areas.

In a diversified farm, the cost-opportunity to learn, use, maintain, and repair a new digital technology shall be added to the bill to pay for private insurance, land rents, bank loans, housing, mobility, internet connectivity, packaging material, spending to comply with food safety standards, or energy consumption of rural households in a context of the low margins of revenues from agricultural products.

Ownership and control over the means of production, marketing, and living remains basic conditions for farmers also when internalisation of agritourism services, direct selling, or farm visits goes digital. Otherwise, farmers and communities will be the manufacturing arms of third-party platforms. For instance, “La Clique en Senne” (https://www.la-clique-en-senne.be/) is a group of farmers in Wallonia (Belgium) who organised themselves in an agricultural cooperative and decided to open their own online food platform instead of selling their produce on the various direct selling platforms that are proliferating in the EU.

Building an online platform for multifunctional services today takes less time than building the physical logistics infrastructure needed for rural mobility and businesses. Mutualising risks, sharing costs, and building partnerships are important for localising internalisation before profits go away into the usual big pockets. Though online platforms can be seen as part of the virtual world, much of the transactions are still happening “for real”, with the involvement human labour, energy, and physical assets.

No matter what digital arrangement is found in the sharing economy (e.g., open or encrypted algorithms, centralised or decentralised), the delivery and collection of food require human labour, roads, logistic vehicles, physical environments that are so far used by online platforms thanks to formal and informal partnerships or public avenues on the ground (e.g., churches, bar and café, old buildings, community hubs). This social and physical legacy shall be stressed.

Internalisation: that’s it?

Agricultural multifunctionality as a concept can offer a wide spectrum of actions for diversifying agriculture and farm business. Some of them have already been announced earlier, like the consumer-producer cooperative in Belgium. This group of farmers shows an example of digitalisation and cooperativisation to reach scale and scope.

Cooperatives can make single diversification and digitalisation efforts easier and less burdensome for individual farmers, while gaining ownership and control over the means of production and online marketing. For instance, organic producers, consumers, and restaurants joined together in the Farm-O (https://www.farm-o.net/), an online food platform dedicated to organising purchases, sales, and logistic deliveries of organic products in Kyoto, though this platform is not owned by a cooperative.

Scale remains a crucial factor in providing goods and services efficiently, as well as in building active networks around on-farm diversification. In Belgium, the non-profit association “Accueil Champetre en Wallonie” (https://www.accueilchampetre.be/) has dedicated human and digital resources to strengthen the individual and collective capacity of farmers to adapt their business to the compelling norms and societal demand for farm diversification goods and services. It might sound trivial but simple practical assistance, e.g., on legal and fiscal requirements for direct selling, can be a game changer in farm diversification.

Through their website and social media, Accueil Champêtre animates a community united by common interests. The online platform displays the whole offer of on-farm diversification in Wallonia region, from farm shops, restaurants, to accommodation or space rentals. By creating digital farm profiles with standardised information, Accueil Champêtre helps consumers and citizens to retrieve information and contacts about farm (i.e., increasing searchability).

Conclusions

There are different avenues to turn digitalisation towards agricultural multifunctionality, with a view to increasing organic farming, supporting on-farm diversification, localising food, reducing intensive use of chemical inputs, and so forth. This paper has attempted to examine internalisation as one possible pathway to get there. I invite other scholars and practitioners to discuss these and other points that I might have omitted here, as well as to expand the toolbox of examples in which digitalisation can be applied in on-farm diversification to strengthen multifunctionality.

Given the limited ability showed so far by multifunctionality as a concept to halt mega-trends and turn the overall direction of agri-food policies towards agroecology and diversification, I encourage scholars and policymakers to look at sharper and more ambitious frameworks to address wicked problems in food, agriculture and rural areas (Iannetta et al., 2021).

In my view, things that might look smart at micro-level (e.g., a simple click to retrieve all your data in a farm dashboard or a new drone to spread chemical fertilisers more precisely), should always be observed from a different angle and macro-level perspective (e.g., growing privatisation and financialisation of agri-food sector, higher control or data privacy violation, growing dependency on fossil fuels). Besides this micro- and macro-level perspective, the experience on the ground shows that digitalisation can represent a valuable instrument to express rural community actions and entrepreneurial creativity vis-á-vis worldwide trends of urbanisation and agri-food globalisation.

In terms of policy-making, I believe one of the follow-up questions to ponder is whether we need to be “smarter” and invent new technological solutions to well-known problems, and/or become “wiser” and make political decisions that avoid the underlying problems and reverse the mega-trends that are pushing small-scale farmers to juggle with the new ways they have been offered to internalise externalities as a last resort to survive or disappear.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Yasuo Ohe who facilitated my research in Japan and provided valuable comments to this paper.

Notes

1 Proposal for a Regulation https://climate.ec.europa.eu/document/fad4a049-ff98-476f-b626-b46c6afdded3_en

2 Ciclo di web talk – agricoltura sociale https://www.reterurale.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/24174

References

Augère-Granier, M.-L. (2016) Farm diversification in the EU, Think Tank, European Parliament https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2016)581978

Bock, A. K., M.Krzysztofowicz, J. Rudkin, and V. Winthagen (2020) Farmers of the Future, Brussels: Joint Research Centre, European Commission. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/232686/farmers_of_the_future_final_online.pdf

Debonne, N., M. Bürgi, V. Diogo, J. Helfenstein, F. Herzog, C. Levers, F. Mohr, R. Swart, and P. Verburg (2022) The geography of megatrends affecting European agriculture, Global Environmental Change, 75: 102551. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2022.102551

Dimopoulos, T., J. Helfenstein, A. Kreuzer, F. Mohr, S. Sentas, R. Giannelis, and T. Kizos (2023) Different responses to mega-trends in less favorable farming systems. Continuation and abandonment of farming land on the islands of Lesvos and Lemnos, Greece. Land Use Policy, 124: 106435. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LANDUSEPOL.2022.106435

FAO. (2021). Fostering rural transformation through the Digital Villages Initiative (DVI) in Africa. https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb7970en/

Hubbard, C., and M. Gorton (2011) Placing agriculture within rural development: evidence from EU case studies, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 29(1) http://epc.sagepub.com/content/29/1/80.short

Iannetta, P. P. M., C. Hawes, G. S. Begg, H. Maaß, G. Ntatsi, D. Savvas, M. Vasconcelos, K. Hamann, M. Williams, D. Styles, L. Toma, S. Shrestha, B. Balázs, , E. Kelemen, M. Debeljak, A. Trajanov, R. Vickers, and R. M. Rees (2021) A Multifunctional Solution for Wicked Problems: Value-Chain Wide Facilitation of Legumes Cultivated at Bioregional Scales Is Necessary to Address the Climate-Biodiversity-Nutrition Nexus, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5: 239. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.692137

Jackson, P., M. G. Rivera Ferre, J. Candel, A. Davies, C. Derani, H. de Vries, V. Dragović-Uzelac, A. H. Hoel, L. Holm, E. Mathijs, P. Morone, M. Penker, R. Śpiewak, K. Termeer, and J. Thøgersen (2021) Food as a commodity, human right or common good, Nature Food 2(3): 132–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00245-5

Klerkx, L. (2008) Matching demand and supply in the Dutch agricultural knowledge infraestructure. The emergence and embedding of new intermediaries in an agricultural innovation system in transition, Wageningen: Wageningen University.

Kohtamäki, M., T. Baines, R. Rabetino, A. Z. Bigdeli, C. Kowalkowski, R. Oliva, and V. Parida (2021) The Palgrave Handbook of Servitization, In M. Kohtamäki, T. Baines, R. Rabetino, A. Z. Bigdeli, C. Kowalkowski, R. Oliva, and V. Parida (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Servitization. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75771-7

Lokier, J., W. Morris, and D. Thomas (2021) Farm shop diversification: Producer motivations and consumer attitudes, The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 22(4), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750320985364

OECD. (2020) Rural Well-being : Geography of Opportunities | OECD Rural Studies | OECD iLibrary. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/rural-well-being_d25cef80-en

Ohe, Y. (2019) Community-based rural tourism and entrepreneurship: A microeconomic approach, Community-Based Rural Tourism and Entrepreneurship: A Microeconomic Approach, 1–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0383-2

Susanna, L. K., and K. Tuomas (2022) How Farmers Conceive and Cope with Megatrends: The Case of Finnish Dairy Farmers, Sustainability 14(4), 2265. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU14042265

van der Ploeg, J. D., H. Renting, G. Brunori, K. Knickel, J. Mannion, T. Marsden, K. De Roest, E. Sevilla-Guzmán, and F. Ventura (2002) Rural Development: From Practices and Policies towards Theory, Sociologia Ruralis 40(4): 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00156

Ward, N., and D. L. Brown (2009) Placing the Rural in Regional Development, Regional Studies 43(10), 1237–1244. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903234696

Yoshida, S., H. Yagi, and G. Garrod (2019) Determinants of farm diversification: entrepreneurship, marketing capability and family management, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 32(6): 607-633. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2019.1607676

Zscheischler, J., R. Brunsch, S. Rogga, and R. W. Scholz (2022) Perceived risks and vulnerabilities of employing digitalization and digital data in agriculture – Socially robust orientations from a transdisciplinary process, Journal of Cleaner Production 358: 132034. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2022.132034

Also Check Out:

Rural Japan | Agroecology, Diversification and Digitalisation on Hashimoto Family Farm

Rural Japan | Diversification and Digitalisation on a Dairy Family Farm

“Faster than NASA” – How a Community Broadband Outfit Turbo-Charged Northern England’s Countryside